26 APR – 1 JUN 2024

Would you plug in? What else can matter to us,

other than how our lives feel from the inside?

Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974)

New York-based artist Nina Hartmann uses her practice to excavate arcane historical narratives: covert programs of parapsychological investigation by the US military and related studies within Ivy League universities are at the centre of Experience Machine. As she delves into government databases and corners of the internet where historical fact and conspiracy continue to intertwine, Hartmann deconstructs and reappropriates iconographic strategies employed within opaque networks of dissemination and influence.

Executed using encaustic, vinyl and resin, her paintings and sculptural works diagram clandestine histories and peripheral belief structures to create enigmatic icons of relation. The artist is especially invested in the stranger-than-fiction research that was carried out in the name of prominent institutions, indelibly marking their history while remaining tacitly veiled in opaque archives and databases. Her source material is drawn from caches of public-access information that can be found online, if one knows where to look: she mines the CIA’s Freedom of Information Act Archive alongside message boards and self published websites for imagery to be manipulated into her wall-based sculptures.

Experience Machine takes its name from the thought experiment devised by philosopher Robert Nozick: a brain-in-a-vat style proposition wherein the subject is hooked up to a device that can simulate, with absolute accuracy, a full range of felt pleasures and experiences. All circumstances generated by the machine would be experienced to their fullest scope, with no indication towards their artifice; through this formulation, Nozick seeks to understand the extent to which an incontrovertible notion of reality, extrinsic to our own consciousness of it, ‘matters.’

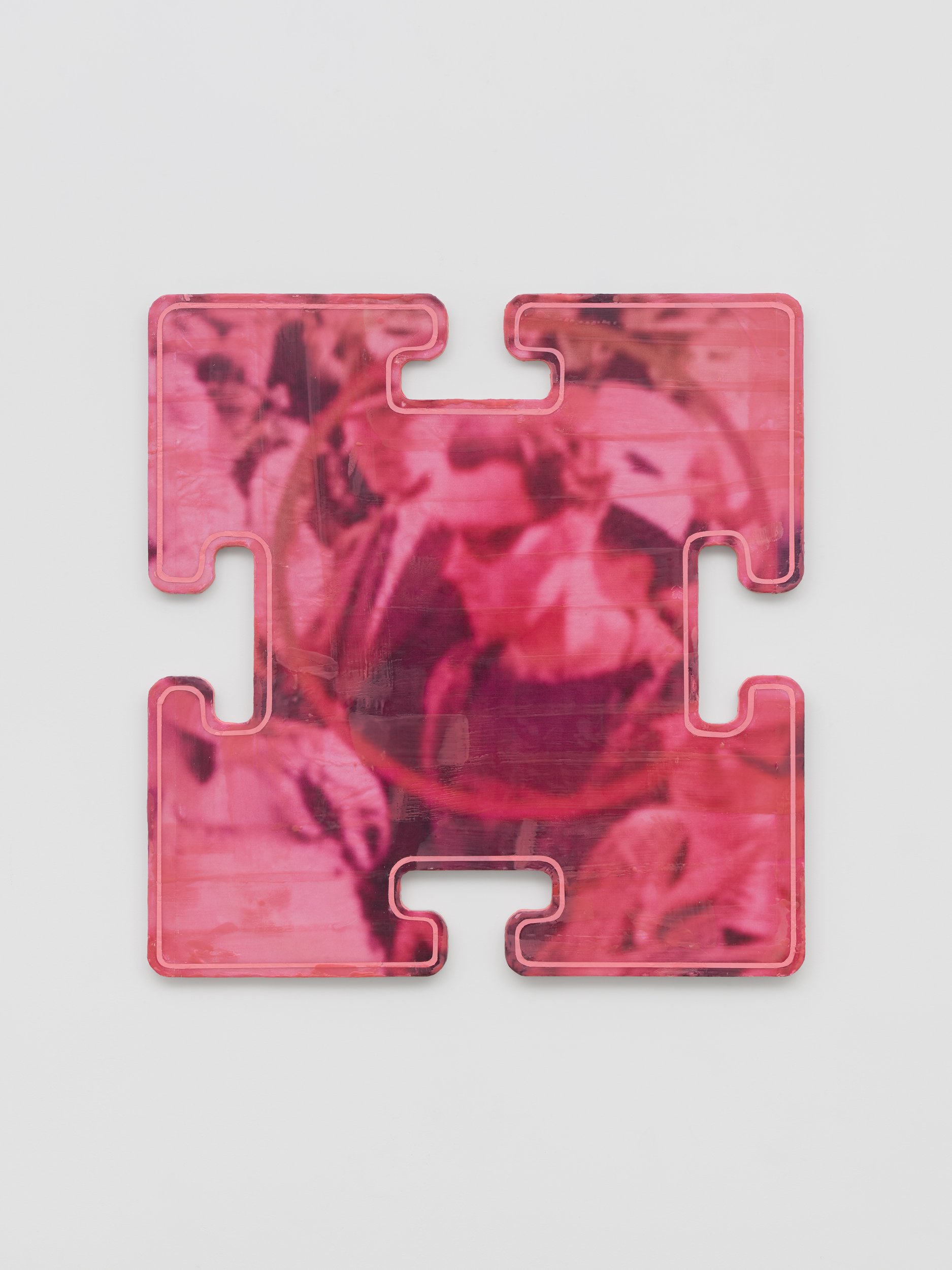

For Hartmann, the phrase ‘Experience Machine’ resonates on multiple registers. The wording, in its suggestion of the imposition of automation on living, feels appropriate to her overarching interest in the invisible mechanisms that quietly shape our daily lives. More specifically, the pursuit of realising versions of this notional machine seems to haunt much of the alternative research and experimentation that she engages through her work. Being familiar with the speculative ties between MK Ultra’s LSD mind control/truth serum research at Harvard University, Hartmann researched the existence of similar programs conducted at Yale, finding several collections of photographic evidence dealing with the work of Dr. Jose Delgado, a former neuropsychology professor. While at Yale, Delgado conducted tests using an invention he called the ‘stimoceiver’ - a device used to stimulate electrical signals in the brain, reportedly able to elicit motor responses as well as ‘pleasant sensations’ including deep concentration, relaxation and euphoria. The image used in Mind Control Image Connectivity (Maze B), 2024 shows a charging bull Delgado allegedly stopped in its tracks using this device.

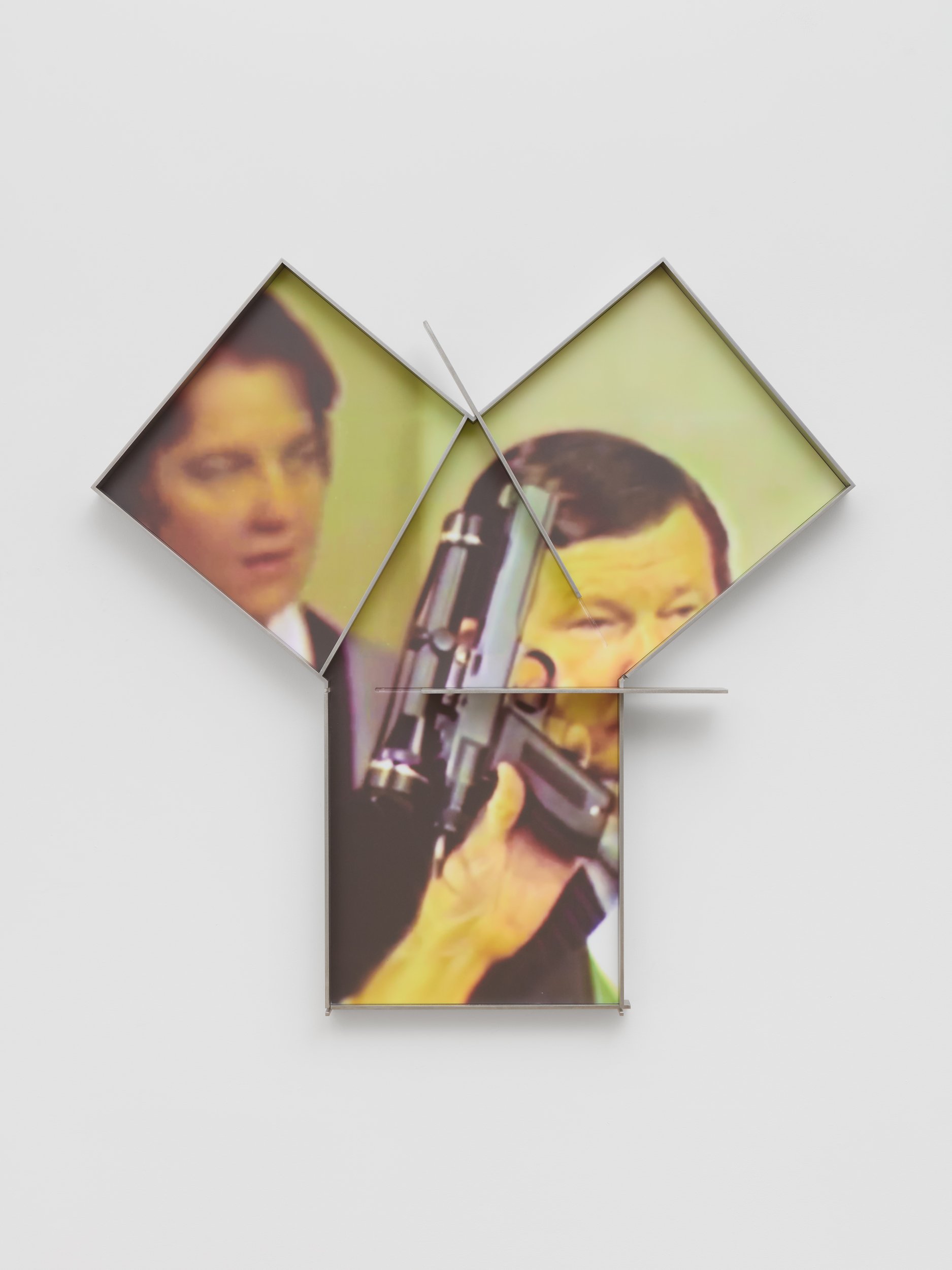

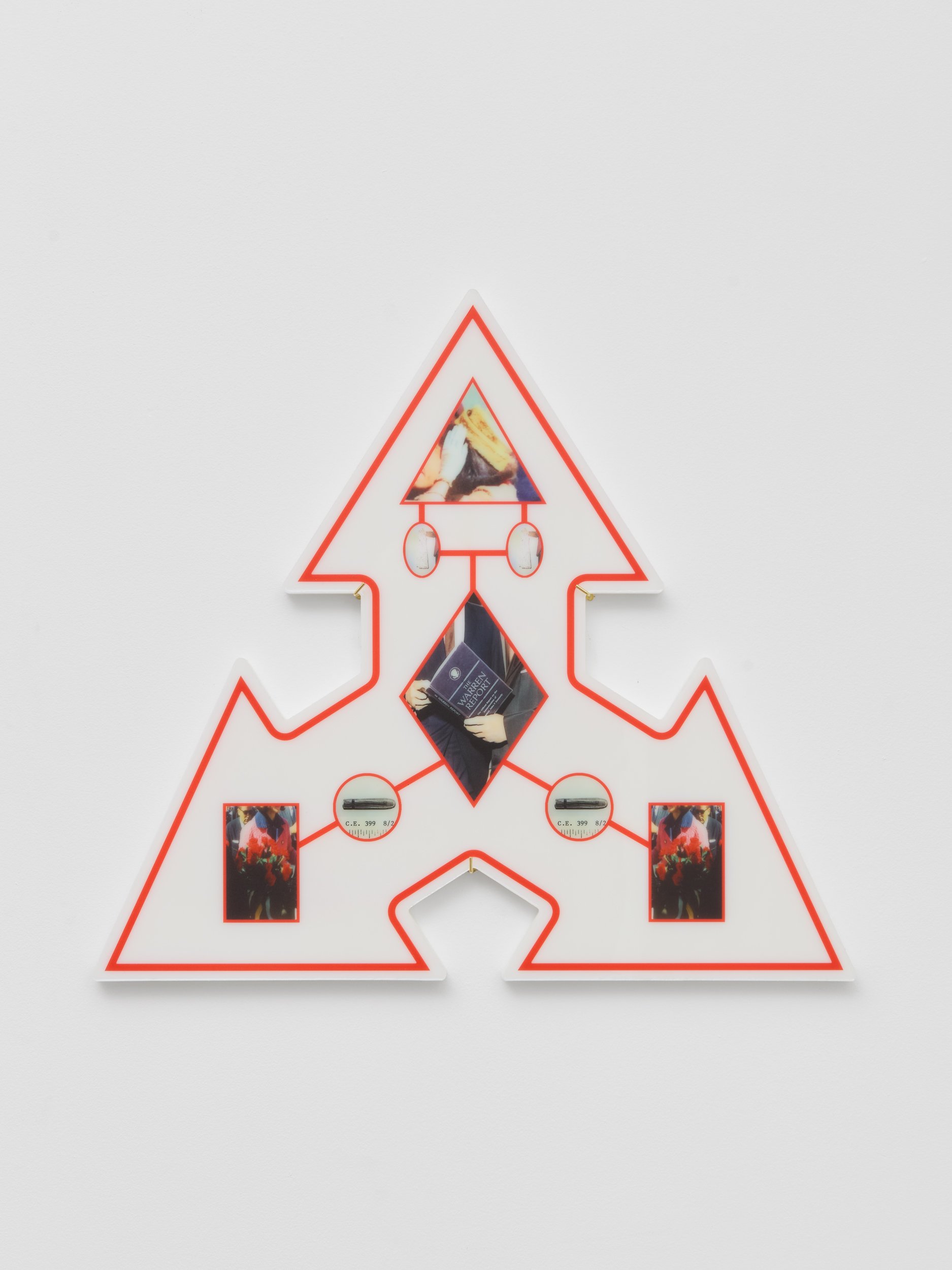

Elsewhere, Hartmann employs the 1941 photograph of a man in anachronistically contemporary-looking sunglasses that went viral as ‘proof’ of time travel; another work depicts an anonymous soldier in the act of flinging a box of propagandistic pamphlets from a plane; works 42 / 82 / 214, 2024 and Networked System of Manchurian Candidate Speculations, 2024 refer to conspiracy theories surrounding the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy. Stainless steel sculptures Heart Attack Gun (Maze A), 2024 and Mind Control Image Connectivity (Maze B), 2024 are inspired by the moveable mazes that test spatial learning and memory in mice, used in experiments surrounding behavioural modification and fear conditioning.

In their composition, many of Hartmann’s works resemble Lacan’s graphing of the subconscious: images are isolated and set within arrows and annotations that map out immaterial networks of fear, desire and power according to an internal logic just out of the viewer’s reach. Here, the lines, arrows and notations marking out spaces are conceptual, as Hartmann uses the schematic visual shorthand employed in the illustration of relationships within quantifiable data to map the inarticulable. For Gilles Deleuze - who the artist cites as a significant influence - the Diagram functions as an ‘abstract machine’: a ‘map of relations between forces, a map of destiny, or intensity’ (Gilles Deleuze, Foucault, 1986). In other words, the diagram form has the ability to express abstract forces at play in the organisation of systems. Hartmann’s works can be seen to embody the diagram’s double bind: in their abstraction, they obscure as much as they explicate. Rather than demystifying the glimpses of narrative gleaned from each fragment of found imagery, the artist’s use of schema functions more like the red string on a conspiracy theorist’s wall of ‘evidence.’ Each annotation, graphic, arrow or segmentation feels like the surfacing of a mycelium network of hidden information, challenging the viewer to enter the paranoid state of meaning-making that leads to conspiratorial rationalisation.